Downside: the UK Church's biggest single heritage challenge

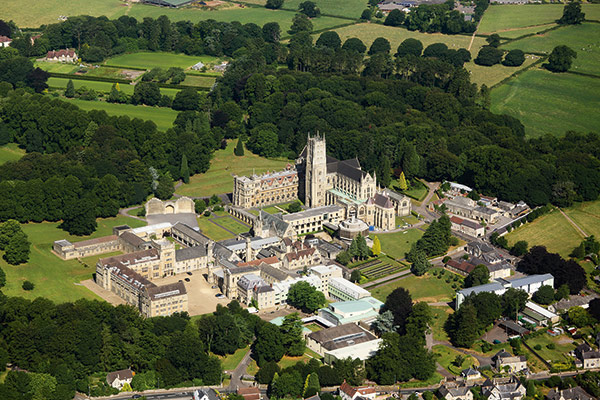

An aerial view of Downside Abbey and Downside School - Alamy/Cambridge Aerial Photography

To some they are defeated old men running away from their problems. To others, they are a spirited bunch making a bold, possibly prophetic move. The Downside monks’ decision to begin a new life in Devon is dividing opinion. Those who take a sour view fear they will not make proper provision for the treasures they leave behind. The more sympathetic believe their mission must come first. Fr Christopher Jamison OSB, Abbot President of the English Benedictine Congregation, put it like this: “They want to embrace the challenges of the mission rather than constantly worry about maintaining the buildings.”

Downside Abbey, standing in 500 acres of Somerset countryside, was once the jewel in the Benedictine crown: a Grade I listed abbey church designated a minor basilica by Pius XI, with magnificent altars and tombs, precious works of art, collections of plate and vestments; the biggest monastic library and archive in the UK; a monastery with public rooms like those of a baronial castle; a public school, with roots in Douai, in the Spanish Netherlands, where the community settled in 1606 and opened a college for the sons of English Catholics. The monks were the first of their congregation to re-settle in England after the Reformation. At Downside from 1814, they built, added to, and embellished their abbey over many decades, commissioning some of the best architects and artists. Downside became a Catholic powerhouse of learning, and excellence in the liturgy.

That time is long past. Just eight monks live in a monastery that once accommodated 50 men. As at the Benedictine monasteries in Ealing and Ampleforth, vocations have all but dried up. But by far the greater blow has been serious criticism by the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA) about how the monks dealt with complaints of child abuse at their schools.

This spring, the Downside community will move to Southgate House, in the grounds of Buckfast Abbey. They will live independently, worship in their own chapel, and be known as the Community of St Gregory the Great. They are led by Abbot Nicholas Wetz, originally from Belmont Abbey, who joined Downside as prior administrator in 2018 and was elected abbot in 2020 for an eight-year term. He says the move is sad but also very exciting. Far from being dejected, he maintains the monks have decided to move while they still have life and energy. The youngest is 31 and the oldest is 86.

Abbot Nicholas says the whole English Benedictine Congregation is trying to discern what to do in a world in which monks are in decline and can no longer teach children. He explains: “Downside has been the first to say, ‘We can no longer sustain this place.’ Working with another community seems to be the way forward. Last summer the monks were able to get out and visit other monasteries. They came back and had lots of questions but didn’t think it was the right time for them to join one of the existing houses, or go off and start something on their own. This is a transitional move and we will use this time, maybe a couple of years, or maybe longer, to decide what to do.”

They have given up their last two parishes, in Suffolk, and retain only their local one, St Benedict’s at Stratton-on-the-Fosse. In the short term, they will serve St Benedict’s at weekends from Southgate. They will not replace the school chaplain when he retires next term. Monastery and school are now run by separate trusts and the relationship between them is that of landlord and tenant. As part of the separation agreement, the monastery, aka the Downside Abbey General Trust, has promised to fund a backlog of repairs estimated at £4 million to historic buildings used by the school.

This is posing a headache for the monks who are asset rich but cash poor. In 2019, they attempted to sell a beautiful fifteenth- century Flemish statue of the Madonna and Child that stands in the abbey church. An Old Gregorian (as old boys are known), Peter Howell, successfully appealed against the decision of the Southern Historic Churches Committee that initially permitted the sale. The community was, however, allowed to sell two, much less valuable, renaissance paintings.

They could raise much of the £4m if they could sell land for development. But their planning application to build 16 luxury houses in Abbey Road, close to the abbey’s original entrance, has upset residents in the village of Chilcompton. Around 60 have sent objections to Mendip District Council. They are unhappy about the development of a greenfield site, claim amenities locally are at full capacity and that large houses are not needed. This plan is linked to a second, to build nine affordable homes at Stratton-on-the-Fosse, but the council’s planning case officer has raised an objection to this proposal. Abbot Nicholas says that if the two applications are turned down, they will appeal: “It will be a huge disappointment if it can’t go ahead and will give me more sleepless nights.”

So far, the repairs have gone ahead as scheduled according to the school’s headmaster, Andrew Hobbs. He is very positive about the school’s future. There are 364 pupils – currently full capacity – in spite of the challenges presented by the Covid-19 pandemic. The school received a glowing report from the Independent Schools Inspectorate in 2018 and describes itself as “the home of Benedictine culture”. Pupils will continue to worship in the abbey church after the monks have gone, as will parishioners from Stratton-on-the-Fosse (their church remains closed).

But who will maintain the abbey church and other historic buildings? A conservation architect told me this is the biggest single heritage challenge facing the Catholic Church in the UK. Sixteen months after the monks first announced they were leaving Downside, there is still no plan as to how to meet this challenge.

Things are moving so slowly that the monks have had to postpone their departure by at least six months. On the plus side, grants totalling £1.4m to Downside Abbey from the National Lottery Heritage Fund (NLHF) have helped to conserve the library and archives. The building has been fully restored, the collections professionally catalogued, and the library is open to readers by appointment. The abbey church is in good shape, with repairs in recent years funded by grants and private donors.

Abbot Nicholas says that after the community leaves, the trust’s staff, consisting of two full-time workers and a large number of volunteers, will continue to look after the heritage assets. He adds that much of the trust’s income – mostly rents from property totalling around £900,000 a year – will go towards maintaining the abbey church and library. “Everybody seems to think we will lock the door and disappear. We are not intending to abandon our heritage legacy in any way,” he says.

The abbot’s sentiments are echoed by the trust’s Director of Heritage, Dr Simon Johnson, who has worked closely with the NLHF on the modernisation of the library. He has a vision of Downside becoming a centre of Benedictine Catholic heritage and is consulting colleagues at the former northern seminary of Ushaw, near Durham, which has undergone a similar change of use. He has also forged links with the universities of Salzburg, Bath Spa and Bristol.

Abbot Nicholas says that the monks are considering the idea of a separate trust to maintain the church but this would not be straightforward as, in canon law, it is part of the “stable patrimony” of the monastery: “Alienation (the handing over to another trust or owner) needs various permissions and, in this case, also the permission of the Holy See. We couldn’t just give it away.”

Another issue is the fate of the monastery itself. Abbot Nicholas does not rule out the possibility that it may be sold. There have been rumours that it could become a hotel or be developed as apartments. Richard Bevan, a chartered accountant, who has just become the first lay trustee of the Downside Abbey General Trust, says this does not form part of their current thinking and would not be its preferred outcome. Fr Christopher Jamison, himself an Old Gregorian, speaks of a careful, slow-burning discernment to find the way forward. He says Historic England, the public body responsible for protecting historically important buildings and their contents, has been positive and helpful as has Sophie Andreae, vice chair of the English and Welsh bishops’ patrimony committee.

Several Old Gregorians with relevant expertise are also eager to help and some are disappointed that they have not been asked. Fr Christopher believes there will be a role for them, but not yet. “The difficulty is if you have too many people offering ideas it becomes very difficult to contain,” he says. But William Filmer-Sankey, an architectural historian and former director of the Victorian Society, who attended Downside in the late-1960s and early-1970s, disagrees: “I work a lot with buildings you have to find new uses for. Early on you have to ask, ‘What are the possibilities?’ You need to get a large group of people in a room exchanging ideas to get the ball rolling.”

Filmer-Sankey, who leads the conservation team at an engineering and design practice with particular interest in the historic environment, recalls a visit to the abbey church three years ago: “At one time, you could sense the dying echoes of Gregorian chant or incense but this time, it was lifeless. It was really, really sad. It underlines the critical need to breathe life back into those buildings.” Filmer-Sankey thinks the abbey complex would be best suited to a religious, lay or academic community, though he stresses the scale of the challenge. He has massive sympathy for the monks: “It is easy to stand on the side and be critical. If we are going to get a solution for the abbey and the abbey church in particular, it has to be done through co-operation and support.”

James Lomax, retired curator of the Leeds museum and gallery at Temple Newsam, suggests there could be an advisory committee of Old Gregorians: “There are several former curators who would be happy to come together to help and advise in different ways. It needs a proper structure, maybe done in collaboration with the library and archive.”

School and monastery are legally separate, but this is notional on the ground as some buildings are shared. Historic England insists that the abbey school and wider estate must be treated as a whole heritage site. It is seeking stringent safeguards for buildings that are of national importance. Abbot Nicholas could be in for more sleepless nights.

Elena Curti is a former deputy editor of The Tablet, and author of Fifty Catholic Churches to See Before You Die (Gracewing, £14.99).

Votes : 0

Votes : 0