Sunni vs Shia: don’t blame the faith, it’s the politics

The Sunni-Shia split

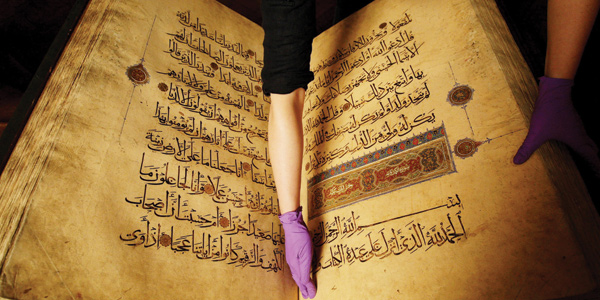

The 1,400-year-old schism between Sunni and Shia Muslims has rarely been as toxic as it is today, feeding wars and communal strife in Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Pakistan, Afghanistan and elsewhere. But what lies behind the Sunni-Shia split? All Muslims agree on the text of the Qur’an as the word of God – but they also ask who to trust as the transmitters of Muhammad’s custom or sunna, which is vital to the practice of their faith.

The divide between Muslims may go back to the lifetime of the Prophet, or at least to his final hours. Different accounts of who held and comforted Muhammad as he died have survived. Ayesha, the closest of his wives at the end of his life, tells us it was her. But Abdullah bin Abbas, the Prophet’s cousin (and ancestor of the Abbasid caliphs), insists it was Ali, another cousin, who was married to the Prophet’s daughter, Fatima, and was the father of his grandchildren. We cannot know which account is correct.

Three things are certain: Ali and Ayesha were both very close to the Prophet; each loathed the other; and Ali believed that Muhammad intended him to lead the Muslim community when he died. That, however, was problematic since Muhammad’s tribe, the aristocratic Quraysh of Mecca, was determined to keep the leadership in its hands.

Ali was perceived as too close to non-Qurayshis to guarantee this. That is probably why it was Abu Bakr, not Muhammad’s son-in-law, Ali, who became the first caliph, or successor to the Prophet. Abu Bakr was Ayesha’s father. After Abu Bakr’s death, Ali was passed over again in favour of two other early companions of the Prophet: first Umar and then Uthman.

It was only when Uthman was murdered in a dispute over revenues from the territories that the Muslims had conquered since Muhammad’s death that Ali was finally acclaimed as caliph. Ayesha immediately stirred up a rebellion against him. Ali crushed this without too much difficulty. But he could not assert his authority over Mu’awiya, the powerful governor of Greater Syria who was a kinsman of the murdered Uthman. When Ali was assassinated by a disgruntled former follower who had repudiated his leadership, Mu’awiya became the first caliph of the Umayyad dynasty.

This little slice of history brings us to the nub of the question: if Muhammad had intended Ali to lead the community, how could leading companions of the Prophet, such as Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman and Ayesha, be trusted to transmit the Prophet’s sunna? They had conspired to thwart the Prophet’s choice. If, on the other hand, Muhammad had not intended Ali to lead the community, how could Ali and his descendants claim the status to which they considered they were entitled?

For those who believed that Muhammad had intended Ali to lead the community, leadership could only be provided by the head of the house of the Prophet in each generation. He was known as the imam. The imam had an innate religious knowledge that gave him an authority which other Muslims did not possess.

This is the essence of the split between Sunnis (who follow the Companions as the transmitters of the Prophet’s sunna) and Shias (who follow the guidance of the imam from the Prophet’s family). One branch of Shias, the Ismaili disciples of the Aga Khan, still follow the leadership of a living descendant of Muhammad. Yet most Shias today are “Twelvers”: they believe the twelfth imam went into hiding or “occultation” in the ninth/tenth centuries. He is secretly present in the world, and will reappear at the End Times. Over the centuries, many of his functions, such as administering justice, leading the Friday prayers, distributing alms and proclaiming jihad, have increasingly been performed by the religious scholars.

This process could be said to have reached its ultimate conclusion in Iran in 1979, when Ayatollah Khomeini took over the governance of the state following the Islamic revolution. But it is important to stress that Khomeini’s teaching, known as velayate-e faqih (guardianship by the Islamic jurist), is extremely controversial among Twelvers. It may not prevail, and might disappear if the current regime in Iran ended. It is rejected, for instance, by Ayatullah Sistani, the highly regarded spiritual leader of Iraq’s Shia Muslims.

The absence of the imam during his occultation means that, to a non-Muslim, the differences in the teachings of Sunnis and Shias look pretty minor. Ecumenically-minded Sunnis have sometimes suggested that Twelvers should be recognised as a fifth orthodox school alongside the madhahib, the four schools or “rites” of Sunni Islam, which acknowledge each other’s validity. The problem for Twelvers is that this would reduce their divinely-guided imams to the level of the great Sunni scholars – which they would see as blasphemy. Sunnis, for their part, see the status that Shias give their imams as blasphemous.

Nevertheless, even if the rival stories of Ayesha and Ali cradling the dying Muhammad suggest that the split can be traced back to the Prophet’s lifetime, it took several centuries to become formalised. Sunnism and Shi‘ism overlap, intertwine and blend. Impeccably Sunni collections of traditions of the Prophet include the story of what Muhammad said at the pool of Ghadir Khumm, which can be interpreted as indicating that he intended Ali to lead the community after his death. The sixth Shia imam, Ja’far as-Sadiq, taught Malik bin Anas and Abu Hanifa, founders of two of the four Sunni schools that remain vibrant to this day.

They had immense respect for Ja’far. In the early thirteenth century, the Twelver scholar Allamah al-Hilli brought judicial reasoning into Shi‘ism by the process known as ijtihad. He openly acknowledged his debt to the Sunni scholar al-Shafi’i and saw no problem in doing so. Like Shias, Sunnis revere the memory of Hussein, the Prophet’s grandson who was killed at Karbala while attempting to claim the caliphate from the Umayyads after the death of Mu’awiya. At various points in Islamic history, they have joined in the Shia lamentations for his death. In the same way, they venerate the other imams, although they reject the special status that Shias give them.

Sunnis and Shias have not always been at each others’ throats. For well over a hundred years, from the mid-tenth century, most Muslims were ruled by Shias for the only time in Islamic history. However, the Fatimid caliphs in Cairo seem to have had little interest in converting their Sunni subjects to their own Ismailism, while the Twelver Buyids, who made the Sunni Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad a puppet institution, did not attempt to abolish it. Instead, they deposed caliphs at will and replaced them with more pliable successors, while glorying in their title as commander of the caliph’s armies. They were more concerned with the Fatimid threat. Sunni and Twelver scholars worked together to cast doubt on the genealogy of the Fatimids as descendants of the Prophet.

Despite this, the Safavid dynasty used coercion to convert Iran to Twelver Shi‘ism in the sixteenth century. Sunni Ottomans and Shia Safavids then employed sectarian rhetoric when at war. However, the Ottomans only persecuted Shias in their empire when they appeared to be a threat, or in order to exact revenge. In the early sixteenth century, Sultan Selim the Grim massacred tens of thousands of Qizilbash Shias in Anatolia because he feared that they would rise up in favour of the Safavids. An exception that proves the rule was the execution of a governor of Baalbek who came from the Twelver Harfush clan shortly afterwards.

This did not prevent the Ottomans from appointing other members of the same family to the governorship off and on until the nineteenth century. By that time, Muslims were concerned with the challenges posed by the West and were adapting to the new world that confronted them. This tended to bring Sunnis and Shias together rather than further divide them. Shia tribes rallied to the Sunni Ottoman flag to fight the invading British in 1914, while Sunnis and Shias in Baghdad united to oppose direct British rule at the end of the First World War.

Largely Sunni Pakistan was founded by a Shia, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, and few seemed to notice. Before the 1970s, both Sunnis and Shias were drawn to secular ideologies. But not everything was rosy in the garden. Iraq’s Shia majority felt excluded by a predominantly Sunni elite, while the Sunni majority in Syria disdained the Alawi minority that has supplied the country with the Assad dynasty that has ruled since 1970 (Alawis are an esoteric offshoot of Twelver Shi‘ism). Syria and Iraq were (and are) among the most secular Arab countries.

Yet when dictators who came from minorities squashed all dissent, they used patronage to cement their rule – and this tended to benefit disproportionately members of their own communities. This ineluctably opened the way to sectarian politics. Alawis figure disproportionately among the Syrian army’s top brass and those who staff the regime’s torture chambers, while Saddam Hussein’s ruthless republican guard was recruited from Sunni tribes near his (Sunni) home town of Takrit. Nevertheless, it is often forgotten today that the Sunni Islamist uprising in the Syrian city of Hama in 1982 was inspired by the Iranian revolution, while Saddam Hussein feared a united front of Sunni and Shia Islamists more than anything else. Iran is also a key supporter of Hamas, the Sunni Islamist movement in Palestine.

The country that carries most blame for the growth of today’s sectarian hatred is Saudi Arabia, which used the oil boom of the 1970s to spread its anti-Shia, Wahhabi ideology among Muslims everywhere. This is the main influence behind what is now known as Salafism – a form of Islam that attempts to return to the Islam of the salaf, the Companions of the Prophet (literally, “the forebears”). By formalising the status of the Companions in this way, Salafis risk excluding Shias. Some Salafis revive previously half-forgotten texts by firebrand scholars such as Ibn Taymiyya (who died in 1328), and declare Shias worthy of death as renegades.

Hard on Saudi Arabia’s heels in the blame stakes comes Iran, its rival. Iran has attempted to spread its revolutionary ideology among all Muslims – Sunnis and Shias alike – but tries to use Shia communities as proxies. Although the Islamic Republic has taken steps to mollify Sunnis, such as forbidding the traditional Twelver cursing of Ayesha, Abu Bakr, Umar and Uthman, this struggle for hegemony has fuelled sectarian strife in Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iraq. It also led to the emergence of Hizbullah, the powerful Twelver political movement and militia in Lebanon.

In Yemen, a country with no history of sectarianism, competition for influence between Saudi Arabia and Iran has fuelled a bloody civil war and risks opening up a gulf between the Zaydi Shia minority (Zaydis are not Twelvers – and in many respects are much closer to Sunnis) and the Sunni majority.

Third in the blame stakes are the American-led coalition partners that invaded Iraq in 2003 and the neo-conservatives and advocates of “America first” who egged them on. They unwittingly poured kerosene on to the already igniting embers of Sunni-Shia sectarianism.

Before the late-1970s, few in the West outside Islamic studies faculties in universities had heard of the Sunni-Shia divide. Now, it was suddenly and simplistically seized upon as a root cause for everything wrong in the Arab and Muslim worlds, conveniently exempting others from culpability. Sub-dividing people in a far-away and ancient lands into banal categories gave commentators and policymakers the illusion of understanding them and of being sympathetic to their (imagined) aspirations.

It has not been theological differences that has led to the recent bloodshed but the manipulation of identity politics for political ends and the frustration of emerging democracies by repression and the power of patronage. In the end, it was not the neo-

conservatives in Washington but the followers of Islamic State – a murderous offshoot of ultra-Salafism – who almost succeeded in dividing Iraq along sectarian lines.

Are there now signs that the politics of sectarianism have peaked in the Middle East? The half-reasonable performance by nationalist and secular elements in the Iraqi elections may be a straw in the wind. Many people in the region are fed up to the teeth with sectarianism. They long for a return to the largely peaceful co-existence of the many branches of Islam in the past. But will they succeed in overcoming the influence of powerful, vested interests? Ask the question again in five years’ time.

John McHugo is a historian, Arabic linguist and international lawyer. His books include A Concise History of Sunnis and Shi‘is (Saqi Books, £20; Tablet bookshop 020 7799 4064, price £18).

Votes : 0

Votes : 0