Vietnamese priests keep in step with foreign missioners

After the communists expelled all foreign missionaries in 1975, the Vietnam Church developed strong local roots

A Hmong woman and her child on their farm in Lao Cai province in northern Vietnam, where local Catholic missioners are working hard to help people and revive faith. (Photo: UCA News)

In the northern hills of Vietnam, Father Joseph Nguyen Tien Lien starts his day at 4am and finishes at midnight.

The 42-year-old was assigned to Mai Lien Parish in 2017, a year after he became a priest. He came to the hilly Mai Son district of Son La province as the first priest of the newly established parish, which comes under Hung Hoa Diocese.

Evangelizing ethnic villagers “is my top priority. I want to bring God’s love to them so that they can enjoy divine mercy,” he says.

Local priests like Father Lien manage the Catholic parishes and mission station in all 27 dioceses of Vietnam, where Spanish and Portuguese missionaries brought the faith in the 16th century.

The Catholic mission suffered because of a dearth of priests and infrastructure in some 10 dioceses in northern Vietnam, where communism forced Christians to flee during the Vietnam War (1954-75). However, native priests are now enthusiastically engaged in missions, particularly in the north.

Father Lien said ethnic villagers in Son La province “live in misery and suffer many difficulties” such as inadequate food and lack of facilities for education and health care.

Most ethnic groups have large families with several children and they traditionally cultivate crops such as rice and corn in the hilly tracts, lacking sufficient food throughout the year.

The province is home to the Kinh majority and ethnic groups such as the Hmong, Dao, Muong, Thai, Tay and others.

Villagers in northern Vietnam in their traditional clothes attend the 125th anniversary of the establishment of Hung Hoa in the Bishop's House in December 2020. (Photo: UCA News)

The blood of missionaries

Father Lien pays regular pastoral visits to Hmong villagers. He has built 13 chapels in their villages and even helps repair homes damaged by natural disasters. A parish charity group also provides food at four public hospitals on a weekly basis.

“We try to give as much succor as we can to people in need, although we also live with limited means. We long to make contributions to social development,” Father Lien said.

The priest said he was elated at the results. “Over 700 people, most of them Hmong villagers, in this isolated rural area have embraced Catholicism during the past four years. Thank God.” The parish now has 1,600 members.

Father Lien holds summer catechism courses for the locals at his church. Some 100 Hmong villagers attended the one-month course last March. They were provided with food, accommodation and travel allowances.

“We try our best to bring Catholicism to other people in this area as a way to show our deep gratitude to foreign missionaries who introduced the faith to local ethnic groups in the early 20th century,” he said.

Father Lien said he is inspired by foreign missioners who won ethnic groups’ hearts by living among them, adopting ethnic languages and cultures and looking after their material and spiritual needs. They paid pastoral visits to remote villages and fostered harmonious relationships with the villagers.

The first Catholic parish in the area, which would become Hang Hoa Diocese, was established in the 19th century when missionaries from the Society of Foreign Missions of Paris (MEP) started Sapa Parish based in Sapa town in Lao Cai province.

It initially aimed to provide pastoral care for French tourists and then included Hmong villagers, who lived in leaf houses, cultivated crops and raised animals for a living.

Five missionaries served the parish until 1948, when the last one, Father Jean Pierre Ydiart Alhor, was beheaded inside the church.

Father Alhor was buried near the tomb of Bishop Paul-Marie Ramond beside the church. Bishop Ramond, also an MEP missioner, led Hung Hoa Diocese from its establishment in 1895 until his retirement in 1938. He spent his last years in Sapa and died in 1944.

.jpg)

Hmong people are baptized in Hau Thao Church in 2020. (Photo supplied)

Post-war revival of the Catholic faith

The church facilities including the bishop’s house built by foreign missioners were destroyed in fierce battles between French troops and communist forces from 1946-54.

Many Catholics moved to the south, while the rest suffered religious persecution and lived their faith secretly without priests for five decades. Many church facilities were confiscated or ruined.

The parish had no religious activities. Later, when the war was over, many of them returned and started living in the church compound. The church and parish house were used as a school and warehouse.

The stone church built in 1926 was badly damaged in the wars. Three priests paid pastoral visits to local Catholics from 1998 to 2006, when Father Peter Pham Thanh Binh was assigned as parish priest.

Father Binh was among the dozen native seminarians who were sent to study at formation houses in Ho Chi Minh City from 1992 to 1998. He was ordained eight years later after overcoming the obstacles caused by government policies.

The local Catholics had scattered. They were not educated in the catechism and the infrastructure was in poor condition. “I studied the parish history and paid regular visits to ethic villages, learning their language, respecting their culture, and improving their material and spiritual life,” the 50-year-old priest recalled.

Kinh people mainly reside in the town and make a good living by providing services to tourists including running restaurants and hotels.

The Hmong lived in remote villages in the hills, far away from the church. They had large families and children left schools to support their families and marry early in their teens.

They live in poverty, lacking food, clothing and other basic needs to survive. They would borrow money from the priests to pay for medical emergencies.

The Hmong people enjoy cultural festivals like Gau Tao, held in the first month of the lunar new year, and Cho Tinh or love market held on weekends.

Father Peter Pham Thanh Binh welcomes visitors at Sapa parish house. (Photo supplied)

The birth of MEP for Vietnam

The Sapa church has been a center of such activities. In front of the church on weekends, young couples in traditional attire would sing, play musical instruments and dance, drawing a significant number of domestic and foreign visitors interested in their ethnic traditions, customs, food and handmade products.

Father Binh, who is fluent in the Hmong language, said he set up a daycare center and a hostel to help ethnic students pursue their high school studies. This helped sow the seeds of vocations among the young people.

The parish has produced a priest and two sisters who are ethnic Hmong.

Father Binh said it took the parish a decade to help families who lived in the church compound to move to other places. A new pastoral building was completed in early October to meet local people’s religious needs and provide accommodation for retired priests.

The priest, who heads the Ministry Committee for Ethnic Minorities in Hung Hoa Diocese, said he tries to build and upgrade old church facilities, restore old subparishes and develop Catholic associations.

The priest said Sapa district now is home to 4,300 Catholics out of a total population of 66,000 spread across four parishes and a dozen subparishes and mission stations. That’s more than 400 percent growth in 15 years. The district had only about 1,000 Catholics in 2006.

The native missionary, who serves as head of Lao Cai-Lai Chau deanery, also spent 10 years offering pastoral care to Catholic communities in the neighboring provinces of Dien Bien and Lai Chau. It took him one week to travel 1,000 kilometers to visit them. Resident priests were sent to these parishes only in 2016.

“I am inspired to work among the ethnic villagers by the shining examples set by foreign missionaries who sacrificed their lives for them, preserved their cultures, improved their lives and served their needs,” he said.

In 1658, Pope Alexandre VII named French priests François Pallu and Pierre Lambert de la Motte as apostolic vicars in Vietnam and southern China.

One year later, two dioceses were established in Vietnam and the missioners were elevated to bishops. Bishop Pallu headed the new Dang Ngoai (Tonkin) covering northern Vietnam, Laos and parts of China, while Bishop de la Motte led Dang Trong (Cochinchine) covering southern Vietnam and parts of China.

The two bishops along with others founded the MEP to send missioners to work in Asia. They also began training missioners for the region as early as 1659. In 1662, Bishop de la Motte and two priests landed in the then capital of Ayutthaya in Thailand followed by Bishop Pallu and four other priests two years later.

In 1668, Bishop de la Motte ordained the first Vietnamese priest, Joseph Trang, in Thailand. Father Trang was then aged 29. Three other priests from Vietnam were ordained that same year, marking a milestone in the growth of the Church in Vietnam.

Bishop Jean Cassaigne (1895-1973) of Saigon and his ethnic K'hor villagers who suffered leprosy on his ordination in Saigon on June 24, 1941. The French missionary lived among ethnic lepers for 32 years and died in 1973 in Di Linh. (File photo)

Reviving faith in the hills

Many MEP members were assigned to train local clergy, provide pastoral care for Catholics and bring Catholicism to the locals, especially ethnic groups in remote areas. They also established some religious orders to work among local people.

Catholic missionaries contributed to local culture and literature when they translated Bibles into Hmong and composed books of prayers in Hmong.

A Hmong Catholic from Phinh Ho Parish in Yen Bai province said many villagers were baptized by late French Father Paul Doussoux Hien, who established the parishes of Phinh Ho and Dong Lu for Hmong villagers in the early 1900s.

She said they looked after the church and gathered local people for daily prayers for decades without priests. They taught the Bible, hymns, prayers and catechism to others from other places. Those who finished courses returned to lead prayers in their villages.

As a result, the seeds of Catholicism have been transferred by ethnic generations, she said. Her Phinh Ho Parish had no priests until 2013, when priests from the Congregation of the Mission were sent to them.

“We now try our best to preserve the faith heritage from foreign missioners and our ancestors despite grave difficulties,” she said.

Phinh Ho Parish, where the first person was baptized in 1917, serves 2,700 members from the districts of Tram Tau and Van Chan. Its wooden church was built in the 1940s.

Father Peter Nguyen Truong Giang, who serves as deputy of the Ministry Committee for Ethnic Minorities in Hung Hoa Diocese, said that early this year a book of prayers was composed in the Hmong script.

Bishop Peter Nguyen Van Vien, the apostolic administrator of Hung Hoa, approved it to replace the old prayer books written in the outdated script.

Father Peter Nguyen Truong Giang (left) and Hmong villagers welcome Bishop Peter Nguyen Van Vien and other visitors at Lao Chai Church in 2020. (Photo: UCA News)

A new era begins

Father Giang, who is fluent in the ethnic language, said some 90 priests, nuns, catechists and lay missioners from Lao Cai province were trained to read Hmong prayers and use it in liturgy.

“We hope the new book will help Hmong Catholics to understand what they read and live out their faith,” he said.

Three northwestern provinces of Dien Bien, Lai Chau and Son La, which are home to two dozen ethnic groups, resumed religious activities in 2000s. They now have 12 parishes and tens of subparishes and mission stations with 15,000 Catholics.

Father Lien said local Catholics maintain good relationships with people of other faiths and the authorities and regularly contribute to improving people’s lives.

Several parishes such as his still await government approval. “We hope our parish will be recognized soon so that we have more favorable conditions to live our faith,” he said.

The last foreign missionary in Vietnam, MEP Father Jean-Baptiste Etcharren, died on Sept. 21 aged 89.

The communists forced all foreign missionaries to leave the country in 1975 after they took power at the end of the Vietnam war. But Father Etcharren, a self-confessed Vietnam lover, came back to Hue in 2010 after the government relaxed some norms in 1991.

He is now buried among 37 other MEP members at the old cemetery in the compound of Hue Major Seminary.

“Now you are laid to rest in this land you loved to the end. A star of the Church in Vietnam has gone out," Father Anthony Duong Quynh, vicar general of the archdiocese, said at his funeral Mass.

Father Etcharren, the MEP’s former superior general, was allowed to return at the invitation of Archbishop Stephen (Étienne) Nguyen Nhu The of Hue.

His death marks the end of an era of foreign missions in Vietnam but also signals the beginning of another, in which local priests are managing their own Church.

Bishop Eugène Marie Joseph Allys Ly (1852-1936) and brothers of the Sacred Heart congregation established by himself in 1927. He was among eight MEP bishops who led Hue Diocese from 1850 to 1960. (File photo)

New seminary for Thai Binh

The 7 million Catholics in Vietnam form 7 percent of its population and they live spread across 2,228 parishes. Some 2,668 local priests like Father Lien take care of their pastoral needs.

In September, the northern Thai Binh Diocese announced it had government approval to establish a major seminary.

Father Thomas Doan Xuan Thoa, head of the diocese’s advisory board, said the seminary will admit students not only from the local diocese but from other dioceses and congregations. It will have facilities to accommodate some 300 students.

The Church in Vietnam currently runs 11 major seminaries with 2,824 students from all its 27 dioceses.

Each year, hundreds of new priests come out of these seminaries to assist missionaries like Father Lien who toil on the plains and hills of Vietnam.

As usual, Father Lien will start work tomorrow before sun rays hit the swirling fog on the hills of Son La province. He knows he is part of a mission that continues.

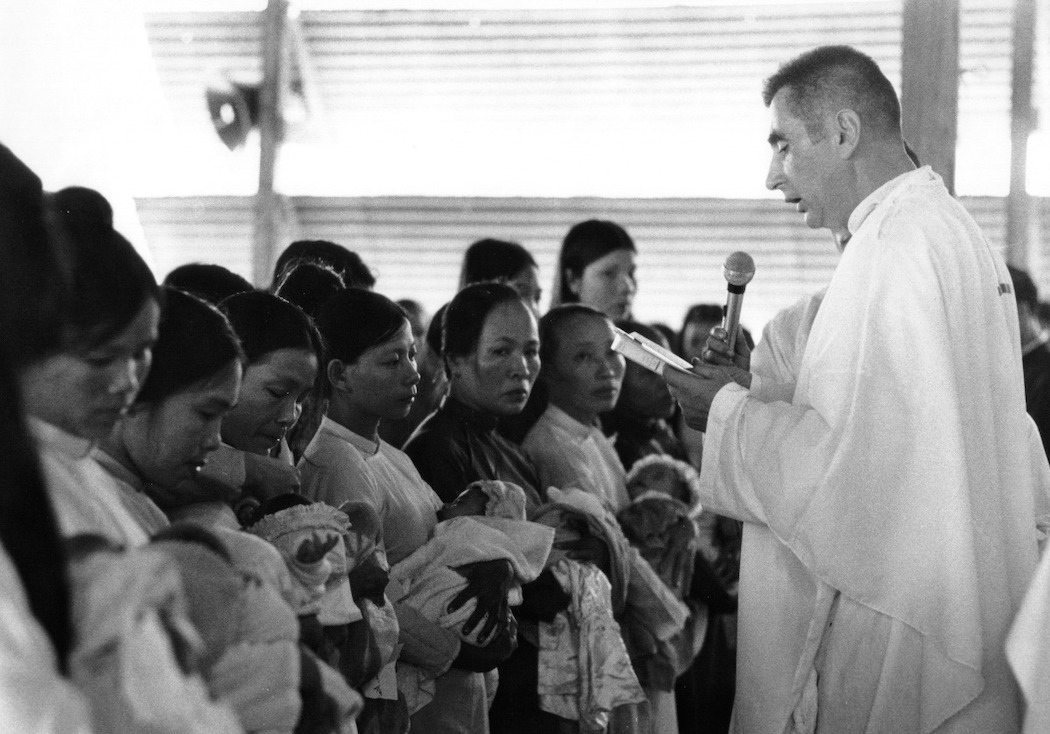

Father Jean-Baptiste Etcharren baptizes babies in Quang Binh before he left Vietnam in 1975. (File photo)

Votes : 0

Votes : 0