When empires collapse – how history is repeating itself in Ukraine

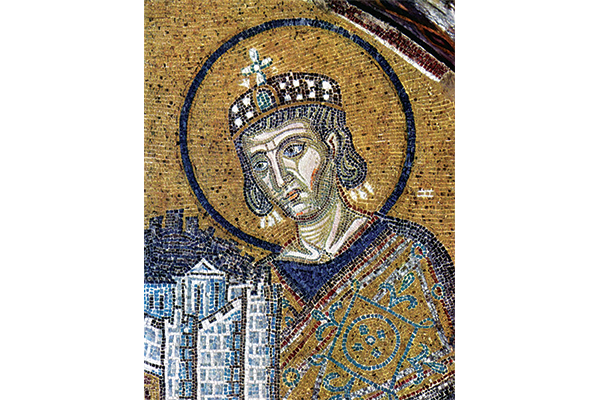

Emperor Constantine: crucial role - Photo: Alamy/ CPA Media

When great empires collapse, and when emperors lose touch with reality, trouble tends to follow. An eminent political historian is not shocked by current events in Ukraine.

A handful of extraordinarily powerful individuals ruled much of the world for over five millennia. For the past six years I have been investigating supreme leadership in differing dynastic, political, religious and cultural contexts – though in many ways my new book, In the Shadow of the Gods: The Emperor in World History, sums up everything I have studied, taught and written about in a career of nearly 50 years. It is in part a collective biography, in part an anatomy of hereditary imperial monarchy as a type of political system and in part an essay on leadership. I study many of the most fascinating individuals, most dramatic events and most significant polities in history. Emperors mattered in ways that still resonate in today’s world.

A crucial example is the close link between emperors and religion. Without Constantine, the marriage of Roman Empire and Christianity, which lies at the core of Western civilisation, might well not have happened. Without the third-century BCE Indian emperor Ashoka, Buddhism would probably have died out or remained a smallish sect in northern India instead of having a huge religious and cultural impact across most of Asia.

Among the recurring themes in the story of emperors and emperorship are legitimacy and succession, the role of religion in politics, managing ministers and bureaucracies and that most ancient of political dilemmas – the stresses and temptations of power. When planning my book, it helped to think of emperors from four angles: they were human beings, leaders, hereditary monarchs and rulers of empire. Hereditary monarchy is the least salient when it comes to understanding the contemporary world. Few contemporary political leaders are hereditary monarchs. Nevertheless the history of hereditary monarchy provides many insights into crucial contemporary issues. It means dynasty – in other words, families in power – and makes biological reproduction the key to legitimate acquisition of power. Over the millennia, men have devised many crafty means to keep females out of bureaucracies, armies and judiciaries but no man has yet been crafty enough to stop women playing key roles in families and reproduction. The female power inherent in hereditary monarchy and royal courts enraged (among others) Scottish sixteenth-century Calvinists, Confucian officials and French Jacobins and was seen by all three as the source of corruption, sensuality and political failure.

At the heart of my investigation is the old debate about the role of the individual in history. A book on this scale has to be organised partly around concepts, generalisations and comparisons. But its core is biography and individuals are notoriously difficult to categorise. Human nature and above all the human mind are not unchanging. I make what might seem a bizarre comparison between the fourth-century Roman emperor Julian (“the Apostate”) and the eighteenth-century Habsburg emperor, Joseph II. Both were intelligent and thoughtful men but their impatience and excitability could sometimes verge on hysteria. Unlike most hereditary emperors, they came to the throne with radical plans for domestic reform. Julian wished to restore paganism and Joseph wished to implement fundamental changes rooted in Enlightenment concepts of utility, uniformity and progress. Both leaders’ domestic reform programme was partly wrecked by aggressive foreign policies. In one sense, the two emperors are fruitful subjects for comparison. But a chasm divided the worlds of classical pagan gods and neo-Platonic metaphysics on the one hand, and the secular, rational and utilitarian Enlightenment on the other.

Human nature and life have some constants, among them the life cycle. Some of history’s greatest dynasties and empires – India’s Mughals and China’s Tang dynasty for example – were wrecked by increasingly stubborn, exhausted and isolated emperors. Some emperors sought the elixir of eternal youth in the arms of young mistresses, with sometimes devastating consequences for political stability. Others, with their eyes on their place in Heaven or in history, lost their sense of balance, perspective and realism. Older veteran councillors, uncles and mothers to whom a monarch might once have listened and even deferred were long since dead. Even more than most leaders, loneliness and isolation are the monarch’s lot. Nothing was more fatal for an emperor than to believe his own regime’s propaganda that he was supremely wise and virtuous, all-powerful, and blessed by Heaven. It took great self-awareness, self-discipline and sense of responsibility for a monarch to avoid this trap after decades on the throne. Dynasties that lasted stressed these qualities above all others in the education of princes.

Unlike contemporary autocratic strongmen, most hereditary monarchies in history were rooted in powerful religious and ethical principles. Even ageing royal autocrats might remain constrained by these principles. Whether ageing emperors like modern strongmen faced looming succession crises depended greatly on whether law and convention defined who was the legitimate heir. Among hereditary monarchies, Latin Europe’s strict and generally recognised system of male primogeniture was exceptional. It risked putting incompetents on the throne but it avoided the devastating succession struggles that weakened and frequently destroyed non-European empires.

Hereditary imperial monarchy flourished in a world in which authority was believed to come from Heaven, antiquity was deeply respected and hierarchy was taken for granted. Democracy was generally perceived to be the road to anarchy. In the ancient world, only Greek thinkers sometimes celebrated democracy, and even Aristotle believed that this was only viable in a city-state. Two millennia of subsequent history seemed to prove that even if city-states could sustain democracy against internal enemies, they could not defend themselves against the far greater resources of external imperial predators. It took the combined impact of the Industrial Revolution and the French Revolution to create a world in which hereditary imperial monarchy was no longer legitimate or even viable.

Sacredness had always been a core element in monarchical legitimacy. In an increasingly secular and individualist culture, it lost its hold on the public imagination. The modern state was simply too huge and complex to be run for decades by a human chosen by hereditary chance. Though sacred hereditary monarchy is mostly a thing of the past, empire is not. To speak of empire in today’s world almost inevitably sparks visions and debates about the European transoceanic empires. The contemporary arguments about slavery and the campaigns to ensure that “Black Lives Matter” reinforce this bias. It is important to remember that other traditions of empire existed and remain very important. Though I discuss the modern Western empires at some length, the great land empires of Eurasia play a bigger role in my telling of the story. Their histories and legacy remain of crucial importance in today’s world. The present war in Ukraine is largely rooted in a Russian nostalgia for empire and in the territorial and geopolitical conflicts that usually erupt when great empires – of which the Soviet Union was a modern variant – collapse. The 50 pages I devote to Russia provide hints about the historical origins and context of the present catastrophe.

Among the regions of the world, only China has three chapters in my book. This reflects the depth and significance of the Chinese imperial tradition both historically and for today’s world. Like the Western transoceanic empires, the Chinese empire was vast in size, ethnically diverse and powerful. Empire has both common elements and many variations. There is a common Chinese imperial tradition rooted in ancient Confucian and Legalist thought, as well as in the evolving institutions and practices of successive dynasties. However, even a cursory knowledge of Chinese history spots the difference between native Han dynasties (above all Song and Ming) and conquest dynasties whose origins lay among the warrior-nomads beyond China’s northern borders (above all Mongol/Yuan and Qing/Manchu). Size was one key difference. At their apogees, the Ming ruled over 3.1 million square kilometres, the Qing over 14.7 million. It matters enormously that the present People’s Republic is the heir of the Qing, not the Ming. I seek to explain how and why empire endured in China and why the non-Han dynasties were able to generate greater military and expansionist power. But the huge role of personality, leadership and chance in this story should not be forgotten.

Frequently in the last three months we hear disbelief that the awful events in Ukraine could be happening in twenty-first century Europe. As in the period before the First World War, generations of peace and prosperity have bred illusions. The history of imperial geopolitics is a useful antidote. We failed peacefully to integrate Christian, European, capitalist and semi-liberal Germany into the pre-1914 world order largely dominated by anglophones. Today’s far more culturally and historically alien China is a much greater challenge. Simultaneously, we will be facing the immense challenge of climate change, which is going to put governments and peoples under enormous though initially unequal pressure across the globe. The next 50 years will probably be more like the first half of the twentieth century than anything experienced by any but the oldest living Europeans.

Dominic Lieven is a fellow of the British Academy and an honorary fellow and emeritus fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge. His Russia Against Napoleon won the Wolfson Prize and the Prix Napoléon. In the Shadow of the Gods: The Emperor in World History is published this week by Allen Lane at £35 (Tablet price £31.50).

Votes : 0

Votes : 0