Christians in Israel Today: Identity, challenges and prospects

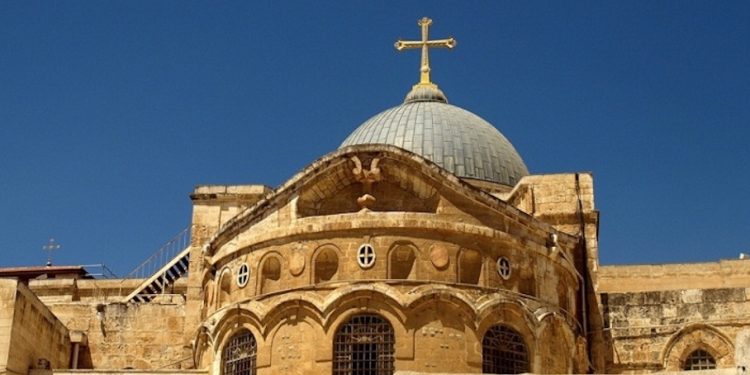

Since the first half of the first century, the Holy Land has been home to Christian communities whose members have played an important role both in the development of Christianity and in the evolution of society in the area. In 1948, with the establishment of the state of Israel, Christians became citizens of a state that defined itself as Jewish. For the first time a Jewish majority held sway over a Christian minority, a new historical reality for both Jews and Christians.

In recent months, the heads of the traditional Christian communities in the Holy Land have clashed with the Israeli civil authorities. Church leaders locally have claimed that “the ancient, indigenous Christian communities in the Holy Land are vanishing fast.” They pointed out, “Today the threat is urgent and existential, with many communities suffering a combination of population decline, intimidation, and challenge for places to live and worship.” According to the Church leaders, radical Jewish Israelis are conducting a coordinated campaign to seize property belonging to Christians, intimidate Christians by means of abuse and violence, and desecrate Christian holy places. They also pointed out that the lack of Christian representation in local government has necessarily led to discrimination against Christians.[1]

On the other hand, the Israeli authorities retorted that the Christians in Israel are the only Christian population in the Middle East that is steadily growing in numbers. Furthermore, they claimed that 84 percent of Christians in Israel were satisfied with their lives as citizens in a Jewish state.[2]

In the light of these conflicting presentations regarding the Christian presence in Israel, one might ask: Who are the Christians in Israel today; what are the challenges they face and what is their future?

Who are the Christians in Israel today?

The territory between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, referred to by many Christians as the Holy Land, is divided today into two different political and legal jurisdictions: the state of Israel, established in May 1948, and the Palestinian Territories (recognized by some as the state of Palestine), comprising East Jerusalem, the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, militarily occupied by Israel in the 1967 War. Christians reside in all these territories but discussion here will be limited to the Christians who reside within the state of Israel and its internationally recognized frontiers, not those who live in the territories under Israeli occupation.

Christian citizens in Israel today make up about 2.4 percent of the population. This constitutes a major decrease in the proportion of Christians when compared with the percentage of Christians in Palestine before 1948, when they constituted about 10 percent of the population. As a result of the war that took place at that time, hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs, Muslims and Christians, left the country as refugees and hundreds of thousands of Jews entered the country as new immigrants. However, today, the number of Christians residing in Israel has almost doubled when Christian migrants who see Israel as home (migrant workers and asylum seekers) are added to the number of Christian citizens.

Christians in Israel belong to an array of denominations: Greek Orthodox, Oriental, Roman (Latin) and Eastern Catholic, Anglican and Protestant as well as Evangelical. Most Christian communities maintain hierarchical structures that predate the establishment of the State of Israel and their heads have jurisdiction beyond Israel’s borders. Many Churches maintain their center in Israeli-occupied East Jerusalem, ministering to the faithful in Israel and Palestine (West Bank and Gaza Strip), with, in some cases, their jurisdiction stretching further afield, including Jordan, Cyprus and beyond.

Whereas denominational diversity is one aspect of Christian identity in Israel today, no less socially and politically significant is their socio-ethnic diversity. About 310,000 Christians live in Israel, 160,000 of them are Israeli citizens and 150,000 are migrants living as long-term residents, with or without legal status.

Christians in Israel today can be divided into four major groups:

1) Christian Palestinian Arab citizens of Israel. Palestinian Arabs who are citizens of Israel constitute about 21 percent of the Israeli population. Most of them are Muslim, but among them there are also populations of Christians and Druze, each constituting about 7 percent of the Israeli Arabs. The majority of Christian Arabs live in Galilee, Haifa and its surroundings and in the towns of central Israel, Jaffa, Ramlah and Lydda. Today, there are about 125,000 citizens of Israel who are Christian Palestinian Arabs. Among them, the vast majority (over 60 percent) are Catholic (belonging to the Greek Catholic (Melkite), Latin and Maronite communities) or Greek Orthodox (over 30 percent). There are also smaller communities of Armenians, Anglicans, Lutherans and Evangelicals.

2) Christian Hebrew-speaking citizens of Israel. Christians who have migrated to Israel because they are of Jewish origin or have marital or other ties with the Jewish people live mostly within Jewish Israeli, Hebrew-speaking society. Most of them emigrated from the countries of the former Soviet Union, Romania, Poland and Ethiopia. Today it is estimated that there are about 40,000 citizens of Israel who are Christians living within the Hebrew-speaking society. Among them the majority are Russian Orthodox (circa 75 percent) with smaller communities of Ethiopian and Romanian Orthodox, Roman and Greek Catholics and Evangelicals. There are also vibrant communities of Messianic Jews (Jews who believe in Jesus). They are not formally linked to any Christian community.

3) Christian migrants. Christians have also come to Israel as migrants: work migrants and asylum seekers – from impoverished countries in Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe and Latin America – or have fled war, oppression and persecution from countries like Eritrea, Sudan and Ukraine. They number about 120,000 labor migrants and 30,000 asylum seekers. Although only a small minority have received permanent resident status, they are an inseparable part of the Christian communities. Among the Christian migrants, there are large communities of Roman Catholics (35 percent), Eritrean and Ethiopian Orthodox, Russian Orthodox, Evangelicals and a plethora of independent church communities.

4) Christian expatriates. Long term resident expatriates who serve in Church structures and institutions form a small but very important part of the Christian presence. Most of the Christian hierarchical Church religious leadership is from this group. For example, the three most senior Church leaders in Israel are all expatriates: Greek Orthodox Patriarch Theophilos III (Greek), Armenian Patriarch Nourhan Manougian (Armenian) and Latin Patriarch Pierbattista Pizzaballa (Italian).

What are the challenges Christians in Israel face?

The Christians in Israel – be they Christian Palestinian Arabs, Christians in Hebrew-speaking society or Christian migrants – face diverse challenges in their daily lives. However, these challenges differ from milieu to milieu. The great denominational, ethnic, linguistic and cultural diversity of Christians constitutes an important obstacle for them to act in unison even when they face common issues like discrimination, loss of identity, migration from Israel, migration to Israel and economic duress. Whereas denominational diversity remains an issue, particularly for the Church hierarchy, the major obstacle to unity among the Christians is the different socio-political milieus in which Christians live, making contact rare and cooperation complex.

Christian Palestinian Arabs in Israel

Christian Palestinian Arab citizens of the State of Israel are part of the Arab minority. They have traditionally played an important role in the life of this minority, disproportionately represented within a highly educated elite of doctors, teachers, social workers, lawyers, engineers, academics and business people. Christian private schools are among the best schools in the country, attracting Christian and non-Christian alike. Christians have been and continue to be major figures in the local Arabic language press, theater and literature. Christians have also played a leading role in the political parties that are active in the Arab sector and in organizations that combat discrimination and campaign for human rights.

The state of Israel defines itself as both a Jewish and a democratic state. Citizens who are not Jewish, however, face various forms of discrimination, constituting a major challenge to their civil rights. All Arab citizens, Muslim, Christian and Druze, are subject to discrimination and marginalization because they are not Jews. The Nation State Law, passed in 2018, once again underlined that Israel is the state of the Jewish people rather than the state of all its citizens. Since 1948, the struggle for equality has been at the center of the life of Arabs in Israel and has strengthened the bonds among Christians and between Muslims and Christians. This struggle has been led by political parties in which Christians have often had a leading role. Generations of nominally Christian politicians have worked hand in hand with secular Jews, Muslims and Druze in the fight against discrimination and marginalization in Israel. Those struggling for equality have also been fighting for an end to the occupation of Palestinian lands after 1967 and the establishment of two states for two peoples. There is a growing number of intellectuals who seek the establishment of a secular, democratic state in all of historical Palestine, ending Jewish hegemony and guaranteeing equality for all citizens.

All those perceived as non-Jews are seen as targets by Jewish religious nationalist extremist individuals and groups, who envision Israel as a Jewish-only society. Spray painting slogans on religious buildings and cemeteries, committing acts of vandalism and spitting at people identified as non-Jews (most often at Christian clerics in traditional robes) are all too common. Whereas these acts are committed by fringe elements, the perpetrators are rarely found and punished. The Israeli education system, particularly in the religious nationalist sector, rarely discusses Christianity and Islam in positive terms, emphasizing rather the Jewish experiences of discrimination and persecution at the hands of Christian or Muslim majorities. Likewise, it tends not to encourage encounters with those who are not Jewish.

A rising Islamic Movement in Israel also challenges Christian Arabs. In recent years, tension based upon the religious divide among Christians, Muslims and Druze has sometimes provoked conflict in Arab localities. Resurgent Islamic activists foment these conflicts, as do certain elements in the Israeli administration, who perceive dividing the Arab minority as a way to maintain Jewish hegemony. The latest series of uprisings in the Arab world, beginning at the end of 2010, has revealed the deep desire of the masses for freedom and dignity but has also opened a Pandora’s box of radical Islamic alternatives to secular Arab regimes, constituting a palpable threat to the Christian dream of equality and integration throughout the Arab world.

The Israeli administration has tended to promote a policy of “divide and rule” with regard to the Arab minority. In the 1950s, the administration invested much effort in separating the Druze (members of an esoteric religious community originating in a split within Shiite Islam in the 12th century) from the rest of the Arab population in Israel. Young Druze were drafted into the army alongside Jews, and the state, with the support of the traditional Druze religious leadership, promoted an approach that defined the Druze as distinct from the Arabs. Similar attempts to separate the Christians from other Arabs failed in that period but these attempts have been renewed in recent years, supported by some Christian Arabs closely aligned to Jewish political interests. Fears of rising Islamic radicalism and promises of material gains for Christians, hoping to end discrimination and integrate within the privileged Jewish sector, encourage some to define themselves as Christian rather than as Palestinian or Arab. Promoting enlistment of Christian Arab youth into the Israeli army and the registration of Christians as being “Aramaic” rather than Palestinian Arab are two forms that this separatist tendency takes.

Some Christian Arab citizens of Israel sense an identity crisis, feeling themselves trapped between Jewish ethnocentric nationalism, which marginalizes and discriminates, and an increasingly Islamic Arab nationalism, which alienates them. The Catholic Church’s Justice and Peace Commission declared in this context in July 2014: “The Church sees her task as one of educating our young people to accept themselves as they are, giving them a balanced human, national and Christian education and an awareness of their history, their rootedness in the land and a sense of identity that integrates the different elements (Palestinian Arab, Christian and citizen of Israel) rather than repressing any one of these elements.”

In facing these challenges, Christian Arabs adopt a variety of strategies in order to survive in Israel:

– Assimilation: some Christians seek to resolve the tension of belonging to a marginal minority by assimilating within the majority. Although conversion to Islam or Judaism is rare, choices of behavior that camouflage Christian identity and underline belonging to the dominant majorities are sometimes adopted. More common is the insistence on being secular and Arab nationalist, focusing on the language, culture, history and socio-political context that Christians share with Muslims.

– Dialogue: the Christian traditional leadership and some of the laity try to engage the majority, predominantly Muslim and sometimes Jewish too, in a dialogue that focuses on the need for respect, equal rights, shared values and, most importantly, shared citizenship.

– Withdrawal: many Christians, in the face of marginalization and discrimination, choose to withdraw from the public sphere and create closed environments where Christians can feel comfortable. Trends in housing and schooling in recent decades have seen the enrolling of most Christian children in Christian private schools rather than in government schools and the creation of housing projects where Christians live apart from their non-Christian neighbors.

– Emigration: some Christians in the face of the challenges of being an Arab and/or a Christian in Israel, choose to seek a better future for themselves and their children in other countries, usually where Christians are the majority. This trend, which began in the 19th century, is one of the most important threats to all the Christian communities in the Middle East today. Those who do leave tend to be the best educated, able to find opportunities in North America and Europe, causing a serious brain drain in the community in Israel.

Christians in Hebrew-speaking society in Israel

Whereas many Christian Palestinian Arabs live in exile, there has been a significant immigration of Christians who have settled within Jewish, Hebrew-speaking society in Israel. Christian members of Jewish families and Christians claiming Jewish ancestry have been migrating to Israel since 1948. Granted many of the same privileges as their Jewish co-nationals, they identify as Jews rather than as non-Jews in the context of the Israeli state.

Today, after the massive waves of immigration from the countries of the ex-Soviet Union (about one million people between 1990 and 2005), there are many Christians who live in the midst of Jewish society in Israel. About 10 percent of the immigrants from the ex-Soviet Union are officially identified as Christians and there might be many more who are Christian without being identified as such. Social pressure to assimilate into the Jewish population is palpable and many hide their Christian identities, adopt Jewish customs and, on rare occasions, even convert to Judaism. The assimilation process is even more successful with the children of these immigrants who are educated in the secular, Jewish Israeli school system, with almost no exposure to the Christian faith and traditions of their parents. Whereas the state promotes conversion to Judaism in general, this is particularly the case within the Israeli army, where young people are encouraged to enter the “mainstream” by becoming formally Jewish. The Institute for Jewish Studies began its work in 1999, and set its sights on converting thousands of non-Jews annually and the Israeli army has its own parallel courses for non-Jewish soldiers.

The new Christian populations constitute a dilemma for a state that defines itself as Jewish. While Christian Arabs are clearly distinguished from the Jewish mainstream because they live within an Arabic-speaking milieu, geographically and institutionally separate from the Jewish Hebrew-speaking milieu, many of the new Christians live at the very heart of Jewish society. The new Christian Israeli citizens make no political demands on the state but do seek full social, economic and cultural integration.

Small signs of recognition of this Christian presence have appeared. One example is that since 1996, Christian soldiers in the army can swear their oath of loyalty to the military on a copy of the New Testament. The challenge for these Christians is transmitting their faith to their children in the midst of a strongly secular and stridently Jewish society. Church structures that were set up to serve the religious needs of this population made Hebrew the language of a Christian population for the first time in the history of the Church.

Christian migrants

Tens of thousands of Christian migrant workers and asylum seekers have boosted the number of Christians in Israel. They have established blossoming Christian communities and makeshift churches in places where the Church had never been present, at the very heart of Jewish towns and cities. Today, south Tel Aviv has one of the largest Christian populations in Israel, tens of thousands of Filipino, Eritrean, Indian, Sri Lankan, Ukrainian, Russian and Latin American Christians, belonging to a plethora of churches: Orthodox, Eastern, Catholic, Protestant and Evangelical, as well a diversity of sects. Although many migrant workers remain in Israel for a limited period, returning to their countries of origin when their permits expire or when they are deported, some migrants have established families in Israel. The children of migrant families have been integrated into the public school system, becoming Hebrew speakers and largely identifying with their country of adoption. The arrival of the children and their schooling has facilitated lengthier stays for their parents even though very few migrant families have been granted permanent residence.

Increasingly, Israel has sought to discourage the stabilization of this population in Israel by withholding social benefits, arresting and expelling some. For Christian migrants, who are not citizens, the precarious living conditions, exploitation in the labor market, lack of social and medical benefits and growing racism (particularly directed against Africans) are enormous challenges. Yet here too, the generation born in Israel is attracted to the vibrant secular Israeli culture and only rarely continues to frequent the Christian communities and churches in which their parents are at home.

For the migrants, frequenting the church brings not only spiritual consolation but also companionship with those who share a language, a culture, traditions and a way of life. Although the migrants bring renewed vibrancy to the churches in the big cities, many find themselves living in places where there is no Church presence and are required to create makeshift communities in rented halls, open lots or in private homes.

Meeting the challenges

Despite the small number of Christians in Israel, the Christian institutional presence is very significant in areas where the Church has been traditionally present, predominantly in the Arab sector. This institutional presence includes schools, hospitals, orphanages, homes for the handicapped and the elderly that catered for Christians and an ever-increasing number of non-Christians. In recent years, the Catholic Church has also established an institutional presence for the migrant population in predominantly Jewish areas (specifically in Tel Aviv and West Jerusalem).

Christian institutions manifest a Church that is active in educational, social and welfare fields. Educational institutions, medical facilities and welfare organisms constitute important arenas in which Christian discourse and values can be promoted in the larger society. The Christian institutional presence in Israel introduces the important reality of a Church that serves all and especially the neediest. As most of the institutions are situated in Arabic-speaking areas, the outreach, beyond the Christian community, is predominantly to the Muslims. However, the work with the migrants has created some links with Jewish agencies as well.

The continued promotion of Christian institutions at the service of the entire population must go hand in hand with the development of an appropriate Christian discourse about the world in which Christians live. It must cultivate a sense of identity and mission that promotes a continued Christian presence in difficult circumstances. It is this discourse that must also distinguish the Christian voice as one that works for justice, equality, peace, pardon, reconciliation, motivated by selfless love. The Christian presence in Israel is not and will not be measured by its statistical importance but rather by the significance of its contribution to society.

What future for the Christians in Israel?

Ongoing discrimination against and marginalization of Christians in Israel weakens already fragile communities. However, Christians are primarily threatened by the ongoing state of war between Israel and the Palestinians. The occupation of Palestinian lands, discrimination against Arab citizens in Israel, violence in the region and socio-political unrest all threaten the welfare of all, including Christians. Prophets of doom predict that the Christians in Israel, in the Holy Land and throughout the Middle East are disappearing and that the day will dawn when there might be no Christians in the area. Educated Christian Arabs are indeed migrating out of their homeland and those that stay are having fewer children. However, new Christian communities are being formed.

Christians have the vocation to contemplate the future with hope, actively responding to the challenges of the present. Such engagement might include the following:

– Christian education needs to deepen a sense of belonging to the land and the particular vocation of being Christian in the Holy Land. This serves to counter the tendency to migrate.

– Christians need to unite more and more, not only across the divisions of denominational identities but also across the socio-political boundaries that originate in the diversity of origins and socio-political contexts. Christian Palestinian Arabs must accommodate the new Christians among them as equal members of the Church and new Christians must get to know their Christian Palestinian brothers and sisters and stand in solidarity with them.

– Christians need to engage in civil society, bringing to it a focus on Gospel values like justice, equality, peace, forgiveness and reconciliation as well as demanding the fostering of a civil society in which citizenship rather than ethnicity or religion define rights and duties.

– Christians need to identify those in society who share their vision, Palestinians and Israelis, Muslims and Jews. Together they can engage in a common struggle for a society in Israel in which freedom, equality, dignity and the respect for human rights are foundational.

– Finally, Christians from Israel are called to play a greater role in the developing dialogue between Christians and Jews. Christians in Israel are in the unique position of being the only Christian minority to live in a state in which the Jews are the majority. Contemporary Jewish-Christian dialogue constitutes one of the most astonishing revolutions in the 20th century, making Christians and Jews partners and allies on many issues after centuries of suspicion and hostility. This partnership might also play a role in bringing justice, equality and peace to Israel, Palestine and the whole Middle East.

DOI: La Civiltà Cattolica, En. Ed. Vol. 6, no.8 art. 3, 0822: 10.32009/22072446.0822.3

[1] These statements can be found on the website: protectingholylandchristians.org/

[2] See the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics report: www.cbs.gov.il/he/mediarelease/DocLib/2021/432/11_21_432b.pdf

Votes : 0

Votes : 0